The Man Behind The Vander Jagt: Wilfred McLaughlin

The Man Behind The Vander Jagt: Wilfred McLaughlin

By: Valerie Van Heest, Lafferty, Van Heest and Assoc.

Wilfred Perrel McLaughlin designed The Vander Jagt in the later stage of the Great Depression and in his early years as a private practice architect when he was just 36 years old. Little has been recorded of his career until the current owners of the Vander Jagt recognized the architectural significance of their home. This prompted research into the career of McLaughlin and the recognition that he played a significant design role in commissions heralded as the work of the more recognized and prolific firm of Benjamin & Benjamin for whom McLaughlin worked from 1925 to 1932.

McLaughlin was born on June 5, 1903, in Niles, Michigan, the second child to Edwin C McLaughlin and Ellen Rebecca Perrell, who had married in 1901. He attended Niles High School and was in the debating club. He graduated in 1920. In the yearbook he was dubbed “the perpetual talking machine.”

He entered the architecture program at the University of Michigan in 1920 at 17 years old. Detroit Architect Emil Lorch served as Dean of the program, which he had started in 1906. (He would serve as Dean until 1940) From the few records that exist, it would seem McLaughlin was an exemplary student. He was a member of the Alpha Rho Chi architectural fraternity throughout college, and he was also in the Tau Sigma Delta Honor Society and the National Honorary Scholastic Fraternity, an organization that recognizes high-achieving students based on academic merit, leadership, service, and character. He graduated in 1925.

During his schooling, McLaughlin interned for the little-known firm of Myrie Smith of South Bend Indiana, some 20 miles from his home, and Francis J. Plym in his hometown of Niles, Michigan. The significance of his apprenticeship for Plym, whose name as an architect is not particularly notable, might be overlooked were it not for the Vander Jagt estate. Plym, who received and degree in architecture from the University of Illinois College of Engineering in 1897, patented a system of metal framing for plate glass storefronts and in 1906 founded what would become the very successful and still operating Kawneer Manufacturing Company, a manufacturer of storefronts and other metalwork (still in business today). He moved the company to Niles, Michigan, in 1907 and later established additional large factories elsewhere. As a recent architecture graduate, McLaughlin was likely tasked to detail custom windows for the firm’s customers. He undoubtedly gained respect for the line of windows, which offered a lifetime guarantee, because some 20 years later, he specified those windows for The Vander Jagt. After graduation in 1925 he joined the firm of Ernest W. Young, a notable architect specializing in several revival styles in South Bend, Indiana. It was here that McLaughlin may have had his first exposure to the Tudor Revival style as Young had received an award and accolades for the 1913 Tudor Revival residence for Mary Louise Hine and had just been hired to design another Tudor Revival home for Andrew C. Weisberg in South Bend (now a landmark home).

The trajectory of McLaughlin’s career from then on can be understood largely through newspaper articles, census documents, and applications for membership to the American Institute of Architects (AIA), and his work, though specific dates are infrequently noted. After a short stay at Young’s firm, in 1925 (or perhaps early 1926) McLaughlin joined the firm Benjamin & Benjamin in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and relocated to a rental home in Grand Rapids. To understand McLaughlin’s career, the history of Benjamin & Benjamin must first be understood.

Thomas Adrian Benjamin, born in 1861 to parents who were among the first wave of Dutch Immigrants to West Michigan, began working in Grand Rapids furniture factories before establishing his own carpentry shop in 1889. According to historian Richard Harms, who undertake with two others a comprehensive study of Benjamin’s early career and nearly 200 of his 300+/-commissions, financial struggles during the 1893 depression prompted Benjamin to diversify, and in 1899 he began advertising himself as an architect under the name Office of Thomas Benjamin, though he did not have any special training in architecture. That was not unheard of in that era before government regulations only allowed licensed architects to use that title. He designed two homes around the turn of the century. In 1904 he established a firm called Alexander & Benjamin to offer real estate services, perhaps developing or buying properties, and providing insurance and loans, which created income even if he had no design and building work.

One of Thomas’s two sons, Adrian T. Benjamin, born in 1882, joined his office as a draftsman in 1906 after three years at the US Naval Academy in Annapolis (1901- 1903) then extensive traveling, and getting married in 1906. The firm then began operating as Thomas Benjamin & Son. His course of study is unknown, but the Navy did not offer an architectural program. Residential commissions picked up that year, and between 1906 and 1909 the father and son produced about 13 homes. As part of business diversification, they began publishing a magazine called Homes in 1906 that only ran one year. The magazine allowed the Benjamins to showcase their home plans, disseminate the latest style trends, and generate revenue by selling advertising space. Perhaps it brought them commissions. By 1909 their work grew tremendously with as many homes built that year as the three previous years. The years 1910 and 1912 were equally busy. Much of that work can probably be attributed to Thomas Benjamin’s real estate business. He became a developer, buying land and selling it to clients who would then hire his firm to design the homes. The firm built numerous homes along both sides of Benjamin Avenue between Wealthy Street and Lake Drive on property owned by Benjamin (originally known as Benjamin Terrace, so named by Thomas Benjamin).

The senior Benjamin made his son, Adrian, chief draftsman in 1910 and junior partner in 1913. At that time the firm also began doing commercial work, including churches, apartment buildings, and several retail and office buildings throughout West Michigan. The Benjamins were Seventh Day Adventists, and the success of their first ecclesiastical commission in1911 for the Seventh Day Adventist Church on Cass Street SE (since razed) not only led to designs for other denominational churches in Washington, D.C., Pennsylvania’ and Florida and would in later years

would propel them (and by association, Wilfred McLaughlin) into designers of much more significant residential projects in the decades to come.

A review of some 175 homes in Grand Rapids designed and likely built by the Benjamins from 1899 to 1920 reveal two to five-bedroom homes in a variety of bungalow, craftsman, American Four Square, and Arts and Crafts styles popular in the early 20th century. Most were built southeast of Grand Rapids on land annexed to the city in 1857 and 1891. At least four of them are within what became known as the Heritage Hills Historic District. The homes were simpler in the first decade of the new century, but became more detailed in the second decade, perhaps a reflection of increasing land prices and a growing economy. A sampling of the homes as they exist today give reason to conclude that they were not custom homes, but rather standard home plans that could be customized with choices of finish and detail, homes that would be called “builder homes” today, rather than “architect designed homes.” Thomas Benjamin was really just a builder, a realization supported by the headline of his obituary in 1950, “Death Takes Ex-Builder.”

During those same years, Benjamin & Son completed only about 30 commercial projects that included the churches previously mentioned, as well as apartment buildings, duplex homes, businesses, and one industrial building. None of these could be considered major high-profile commissions.

America’s involvement in 1917, in what became World War I, led to a slowing of the architectural business. Adrian Benjamin found work as the chief of construction for the U.S. Navy Portable Air stations overseeing the development of over 100 buildings for military use. Thomas was able to build about a dozen homes during the war years and a few commercial projects.

After the war, in May 1919, the Grand Rapids Herald announced that Adrian Benjamin joined offices with architect H.H. Weemhoff, who had gained some local prominence in private practice. The relationship generated some 40 projects in Grand Rapids, (maybe more elsewhere). Ten of those were commercial, so that was an increase in commercial work, but the balance was the same caliber homes Benjamin & Son had previously built. Only two residences in East Grand Rapids were large and unique, suggesting that perhaps Weemhoff was bringing in a higher level of custom home projects. The relationship ended in 1922. It might be surmised they had a falling out because years later when Weemhoff applied for AIA membership, he failed to mention his two-year partnership with Benjamin.

Within about a month of the separation with Weemhoff, Thomas and Adrian reestablished the firm as Benjamin, Robinson & Benjamin, after having promoted their long-time draftsman Karl A. Robinson. Over the next four years of that partnership, the firm reverted to the same type of mid-level homes they had previously been building and completed only three commercial projects in Grand Rapids. That partnership ended in 1924, and by 1925 the father and son reestablished their firm again, this time as Benjamin & Benjamin. When Wildred P. McLaughlin joined the firm that year at just 22, Adrian was 43 and Thomas was 65, and they had a portfolio of some 300 projects in Grand Rapids, and a handful in other cities. Fully 85% of their Grand Rapids projects were single-family homes. The rest were a variety of small commercial projects. Their most architecturally significant projects were the few churches they had designed, and the two larger homes designed in partnership with Weemhoff. All that was about to change.

It is notable that when McLaughlin joined Benjamin & Benjamin, the firm had just been commissioned by W. K. Kellogg, founder of the Toasted Corn Flake Company of Battle Creek, Michigan, and his second wife, Dr. Carrie Staines, to design a summer house on a 32-acre site along the shore of Gull Lake near Kalamazoo. W.K. Kellogg was a Seventh Day Adventist and had surely learned of the firm due to the several Seventh Day Adventist churches it had designed. Seventh Day Adventists tended to support faith-based hiring, a discriminatory practice not barred until the 1960s. Sharing the same faith as the Benjamins likely brought Kellogg a sense of confidence in hiring them. However, there was nothing in the firm’s portfolio to suggest they were capable of the massive estate Kellogg had in mind. Their largest residence up to that point was about a 5-bedroom, 5,000 square feet home, and none of their commercial projects were as large as Kellogg intended for his house. It seems rather coincidental that at that time they hired Wilfred McLaughlin, a young man with a pedigree from the University of Michigan, who had formal training in architecture from a prominent university unlike either of the Benjamins. It is possible that the firm needed him for such a significant project, and it was perhaps the offer to work on that large Tudor Revival, rather than Ernst W. Young’s more modest Tudor Revival, that lured McLaughlin to Benjamin & Benjamin after such a brief stay at Young’s firm.

The Kellogg Manor House, as it would become known, evolved into a 15,000 square foot Tudor Revival style home. That style choice may have been a nod to Kellogg's English heritage. Records indicate Adrian Benjamin served as lead designer for the Kellogg Manor House. While no specific records exist to indicate McLaughlin worked on the project, it is likely that he did due to the timing of his hire. No matter how large or small a role McLaughlin played in that project, he certainly gained an understanding and appreciation for the Tudor style, as he would later design several Tudor Revival homes, including the Vander Jagt.

While the Kellogg project was ongoing, in November 1926 McLaughlin passed his registration exam in Michigan, a state that first offered architectural licensing beginning in 1916 in a program spearheaded by Architect Emil Lorch, coincidently the Dean of Architecture at U of M in the years McLaughlin attended the university. Requirements were not as stringent in 1916. Practicing architects with no formal training could be grandfathered in without passing the exam, as Adrian Benjamin had done, but by 1926, architects had to have a degree in architecture or at least 8 years of experience to become registered.

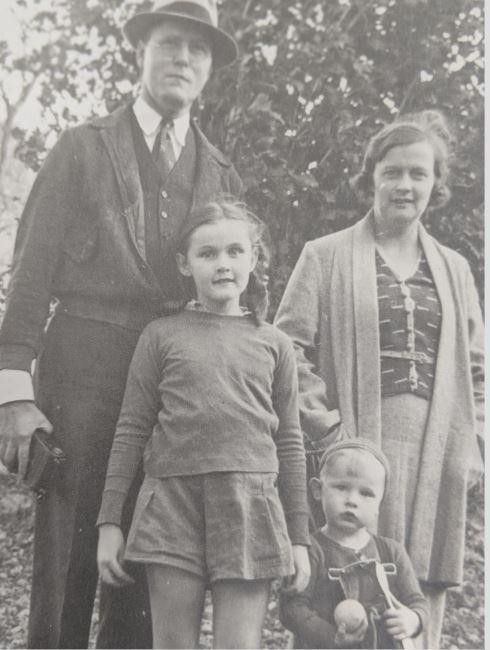

Nine months after passing his licensing exam, McLaughlin married Emma Arlene Sunderlin in August 1927. (They would later have two sons and a daughter). The Kellogg Manor House commission led to other significant sized projects through W.K. Kellogg in Battle Creek, including the Kellogg Hospital (1926), the Boys Club (1926 now listed on the National Register of Historic Places) the Cedar Lake Academy, an Adventist school, (1928) and the Seventh Day Baptist Church (1928). Although records are limited, and McLaughlin’s name is not called out, it can be presumed that he played a role in most if not all projects after joining the firm.

In 1927 the City of Grand Rapids annexed two more small pieces of land east of the city and abutted East Grand Rapids associated with the development of the John W. Blodgett estate on Plymouth Avenue SE, that year. Thomas Benjamin purchased almost all the lots on both sides of Cambridge Street and the west side of Plymouth between Sherman and Franklin Streets, as he had done with Benjamin Street almost a decade earlier. The properties in that area had more value due to their proximity to Reeds Lake and perhaps by developing the neighborhood, Benjamin would generate some work for the firm.

In May 1929, the Grand Rapids Herald announced that Wilfred McLaughlin, who had been with Benjamin & Benjamin for four years, had been promoted to a partner, and the firm would be operating as Benjamin & McLaughlin. Likely Thomas remained active in the role of marketing and real estate development to feed work to his son. Census records indicate that in 1930, McLaughlin and his family were living at 950 Orchard Avenue, East Grand Rapids, a home built that year and perhaps designed by McLaughlin. If the slate walk, seen below, is original, it may be presumed to have been a signature of McLaughlin’s as many of his home designs, including the Vander Jagt, had similar walkways.

Locating residential projects completed by Benjamin & Benjamin after 1925 when McLaughlin joined the firm, as well as 1929 and after the firm operated as Benjamin & McLaughlin has been difficult. The Grand Rapids Public Library has an architect database that provided 17 residential plus several commercial projects. Sometimes the client’s name and address was provided and sometimes only one or the other was provided. Archived newspapers articles found through “McClaughlin” keyword search provided additional projects outside of Grand Rapids. A general google search sometimes offered clues to explore additional commissions. If a client name was provided without an address, then census documents were used to locate addresses. To find the Cannon residence, a newspaper article provided a rendering of the home on Bear Lake, and Google Earth was used to peruse all homes on Bear Lake to seek a home that matched the rendering. The Gordon home was found through similar sleuthing. Although the Seyferth home address has not been identified, it belonged to Otto A. Seyferth, the owner of West Michigan Steel Foundry Inc., indicating how the wealth and position of the firm’s clients had grown, probably from the notoriety following the Kellogg Manor House project. Archived real estate listings and Google Map street view provided images and specifications of the homes. Most are larger, one-of-a-kind, homes, much more architecturally significant than the homes built before McLaughlin joined the firm, further validating the supposition that accredited architect McLaughlin's talents allowed the firm to pursue those commissions.

| Year | Name | Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1925 | 110 College NE Grand Rapids (Dutch Colonial) | |

| 1925 | Harry Rason | 515 Plymouth SE Grand Rapids (Italian) |

| 1925 | Gabriel DeJong | 1001 Alexander Grand Rapids (colonial bungalow) |

| 1926 | Holtman | ? Grand Rapids |

| 1927 | Edward Otte | 1425 Pontiac, Grand Rapids (Tudor) |

| 1927 | Jelle Hekman | 1431 Pontiac SE Grand Rapids (Tudor ) |

| 1927 | Merton Styles former Pratt house | 1927 Madison SE (Italian remodeling) |

| 1928 | Seyferth House | ? Norton Shores |

| 1928 | Lawrence Oliver Gordon | 335 West Circle Dr., North Muskegon (Tudor) |

| 1929 | Kloote | ? Grand Rapids |

| 1929 | Henry Budde | 1939 Wealthy SE Grand Rapids (Tudor) |

| 1929 | Henry Hekman | 1115 Cadillac Dr. Grand Rapids (Traditional) |

| 1929 | Clark Apted | Baltimore NE, Grand Rapids (cape cod colonial) |

| 1929 | W.H. Pleiss | ? Grand Rapids (English country home) |

| 1929 | W. N. Burns | ? Grand Rapids (English manor house) |

| 1930 | John Hekman | 757 Plymouth, Grand Rapids (Tudor) |

| 1930 | Mary and Margaret Mulligan | 2465 Indian Trail SE, Grand Rapids (European) |

| 1931 | Lawrence Oliver Gordon | 480 W. Circle Drive, North Muskegon (Tudor) |

| 1931 | ? | ? East Paris, Grand Rapids |

| 1931 | Philip Snyder | Oakleigh NW, Grand Rapids (early American) |

| 1931 | Earl Dunn | Albert Dr. SE, Grand Rapids (early American) |

| 1932 | Julian Leech | 1744 Alexander SE, Grand Rapids (Tudor) |

For the purposes of the Vander Jagt nomination, only images of Tudor Revival homes (highlighted above) have been included here to consider whether they may have provided inspiration for The Vander Jagt.

The Otte Residence most closely resembles the Vander Jagt with a Dutch Colonial covered porch. The Cannon mansion uses the same stone, brick, and slate roofing materials and masonry detail over the front door seen on the Vander Jagt, though it does not have half-timbering. The Gordon mansion is most similar in design, and setting to the Kellogg Manor House, with its prominent stucco and half-timbering. The John Hekmann House is a one-of-a-kind Tudor with heavy Dutch influence, showing the care shown by the architectural team to individualize their designs for the homeowners.

According to McLaughlin’s AIA application, he left Benjamin to start his own practice in 1932 just shy of his 30th birthday. The reason for doing so is unknown, perhaps the natural progression of a maturing architect. However, more likely the Great Depression may have reduced the partnership’s workload and forced them to go their separate ways, derailing McLaughlin’s career for a time. According to an article published in 2017 by the University of Pennsylvania, many architects struggled during the Great Depression. Some continued to find work through the government in the short-lived Civil Works Administration, the Federal Art Project, or New Deal programs such as the Federal Emergency Relief Administration and the Work Progress Administration (WPA). Architects who adapted to the new budgetary reality designed houses that were not only smaller, but also simpler, with cheaper materials, less demanding craftsmanship, and more straightforward details.

No records have been found for either Benjamin’s or McLaughlin’s independent work in the 1930s, except for McLaughlin’s Vander Jagt. It seems McLaughlin may have done some work for a radio equipment company in South Bend, Indiana, according to public employment documents, but the work he did is unknown. Census records indicate he was still living at his home at 950 Orchard when he began work on the Vander Jagt, and the title block for projects in the early 1940s show that he was working out of his home, suggesting the 1930s had been lean years for him. No matter, his fellow architects, including H.H. Weemhof, who also used to be in partnership with the Benjamins, certainly respected him. In 1939 they voted him president of the West Michigan Society of Architects.

According to their later obituaries, Thomas Benjamin retired in 1934, and Adrian Benjamin practiced until retirement in 1944 at 56 years old, but it appears he did not do any notable projects In Grand Rapids after separation with McLaughlin. Only some records for McLaughlin’s independent projects have been found, perhaps because his work extended beyond Grand Rapids, where it is easier to find past work because the library maintains extensive architectural files. Only the larger and more significant commissions are presented here. From commissions thus far located, The Vander Jagt marked his first project following the Depression. Following that he worked on a number of small, modest homes that he probably just accepted to keep income flowing. Thereafter he seems to have gotten larger commissions, including a 1941 French country estate and a 1942 Tudor illustrated below.

| Year | Name | Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1939 | John Vander Jagt | 2615 Plainfield NE Grand Rapids (Tudor) |

| 1940 | Spec home for Albert Builder | none specified |

| 1940 | Ideal home of 1940 (spec) | 2124 Houseman NE, Grand Rapids |

| 1940 | Bussler | 553 Mulford Drive |

| 1941 | Satin | 1305 Breton East Grand Rapids |

| 1941 | William K. McInerney | 2000 San Lu Rae Dr SE, EGR |

| 1942 | Thomas King | 2600 Coit NE, Grand Rapids (Tudor) |

| 1958 | Louis Eberhard | 970 Santa Barbara, EGR |

| 1959 | Sebastian Family Cottage | 10625 Lakeshore West Olive |

Up until the present, the commission for which McLaughlin is most recognized, simply due to it being his only work that has a presence on the internet (other than the Vander Jagt), is 2 E. Fulton in Grand Rapids, a 2-story commercial building designed for the Davenport Institute in 1949. This Art Deco/Moderne building was originally conceived as a six-story building, but just two floors were completed. The style represents how architects had transitioned to more functional, minimalist styles after the Depression. Today the noted architectural firm of Tower Pinkster occupies space in this McLaughlin-designed building, a testament to the McLaughlin that other architects would appreciate his work.

McLaughlin marriage came to an end in November 1948 soon after the Davenport Institute project was completed. He married again six months later to 40-year-old Edith Clark, and before 1950 they moved into a modest 3-bedroom home at 1129 San Jose Dr. SE East Grand Rapids that McLaughlin might have designed, leaving his first wife at their Orchard Road home with their nearly grown children. He must have kept practicing into the 1950s because in 1952, twenty years after beginning his private practice, he applied for and was accepted as a member to the American Institute of Architects (AIA) and by then had rental offices outside his home. The AIA was founded in 1857 to promote the professional standards and interests of architects. Architects often sought membership for the status that the letters AIA after their names could bring in terms of marketing.

The most recent McLaughlin commission located was the prestigious Sebastian Cottage on Lake Michigan in West Olive. This mid-century style home is a great departure from all the traditional work he was involved with, showing that he responded to the changing times in architecture and did so with the same attention as his earlier work.

Wilfred Perell McLaughlin died in 1960 of unknown causes at just 57 years old after completing the Sebastian Cottage. An obituary in an architectural periodical indicates that during his career he designed over 100 homes, several commercial buildings, and a few bowling lanes and churches. If the obituary is to be believed and includes projects with the Benjamins beginning in 1925, then only 30 of his100 residential projects have been identified. Estimating that McLaughlin was responsible for another 20 commercial projects, that would average about three or four commissions per year over his 35-year career, a reasonable number for a small firm or independent architect.

Based on the high quality of the homes and commercial buildings known to have been designed by Benjamin & Benjamin after McLaughlin joined the firm, Benjamin & McLaughlin (1929-1932), and Wilfred McLaughlin (after 1932) it would seem that he did not receive appropriate recognition for his life’s work, overshadowed by the Benjamins, who were perhaps better marketers and builders than they were design architects. This application has uncovered much more about McLaughlin than previously realized, and it is hoped that listing The Vander Jagt on the National Register of Historic Places will solidify his legacy.